By HARRIETT BURT

Martinez News-Gazette Contributor

Editor’s Note: This is the second part of an article about Robert Semple of Kentucky, the founder of Benicia, who made it possible for another ambitious American from Georgia to found Martinez. Written some years ago for the MHS Newsletter by the late John Bonnell who, in retirement, used his lifelong love of Martinez and his writing and research skills to expand our knowledge about a variety of aspects of our town’s history. For Martinez history, Semple is important because he founded Benicia in 1846 on land originally owned by General Mariano Vallejo who stipulated that not only should the town be named after his wife, but that a ferry service be established between Benicia and Contra Costa (the opposite coast). In Part 1, Bonnell described how Benicia was established. Semple dreamed of creating a great seaport city more important than Yerba Buena/San Francisco which he considered to be nothing but barren sand dunes. That all changed in 1848 when Semple’s ferry changed from an ‘on demand ferry’ that sailed only when there was a passenger to a 24-hour operation with as many as 250 parties lined up on the Contra Costa side to get to the Gold Country. (HJB)

The Gold Rush changed everything on Carquinez Strait

“After gold was discovered at John Sutter’s sawmill on January 24, 1848 Sutter tried to keep the find a secret until he could record his hasty purchase of Indian lands surrounding the site with government authorities in Monterey. In mid-February 1848, he sent two men to do just that. As the men were passing through Benicia en route to Monterey, they fell into polite conversation with some locals while awaiting the ferry. When one of the locals started talking about how lucky a man would be to find coal nearby to fuel ships, one of Sutter’s agents – Charles Bennett – couldn’t contain himself any longer. He pulled out a pouch, dumped about four ounces of gold nuggets and dust on the counter and spilled Sutter’s secret! Within a few weeks most of Benicia’s male population had left for the diggings – the first city in the world to react to the gold discovery.

“Sutter’s purchase of the land surrounding the gold discovery was rejected because Indians couldn’t own land and therefore could not sell it. Semple’s reaction to Bennett’s announcement was cool because he still considered coal more important. Ironically, it was discovered near Mt. Diablo about 15 years later. As Sutter’s men left the ferry and moved south to Monterey they spilled Sutter’s secret again near San Jose and then Gilroy. The gold rush was now underway.

“Mormon promoter Samuel Brannan soon picked up the rumor, made a hasty trip to Coloma to verify it, and then headed back to San Francisco to announce it to the world. While in Benicia, he tried to talk that city’s leading merchant, Edward H. Van Pfister, into going into partnership with him and moving his store to Coloma to “mine the miners”. At first Von Pfister resisted, but after considering how gold fever had stripped Benicia of its mail population and depressed business, he soon changed his mind and chartered Semple’s ferry to take him, Brannan and his merchandise to Sacramento. Brannan led Von Pfister overland from Sacramento to Coloma. Brannan had met Von Pfister in 1846 when the latter happened to be aboard the same ship that brought Brannan and his Mormon emigrant party to San Francisco from Boston. Editor’s note: a significant number of the fortunes if not much of the ordinary money made during the Gold Rush were made by people like Leland Stanford who became rich selling supplies to miners and invested that wealth into building the Central Pacific Railroad (later Southern Pacific) which made him and his two partners even wealthier.

“It took two weeks to load Brannan, Von Pfister and his goods aboard the ferry, travel up to Sacramento, unload and return. The ferry was furthered delayed when it got stuck in the tules on a returning tide. When it finally arrived on the south shore (of the Strait), there were 20 wagons and about 200 men waiting to cross. As rumors of gold spread southward, gold seekers began moving northward to Benicia and eastward to the diggings. Over the coming months the ferry was worked to serve this flood of humanity, often around the clock and sometimes by Semple alone because he couldn’t find any male worker. By mid-1849, “a large number of miners repaired to Benicia, and there pitching their tents, plunged into the most head-long dissipation. Saloons and gambling hells were in full blast, large sums of money being spent on and in these canvas palaces, ornated and embellished in regal splendor.” That situation must have played out, probably on a much lesser scale – on the south shore, where, in May 1849, Col. William M. Smith, married to a daughter of Don Ignacio Martinez, convinced the Martinez family to allow him to develop a new city.

“The city of Martinez thus grew directly out of the Gold Rush activity centered on Semple’s ferry. Indeed, our town’s earliest buildings were clustered around the foot of what is today Berrellesa Street, between roughly Ward Street and the waterfront. In that era the water line came up to about where the railroad tracks are today. (Editor’s note: much of the land north of the railroad tracks is a result of the abnormal amount of soil that was carried by the Sacramento River from the Sierras during and after the gold mining period, particularly in the late 1850s after large mining companies took over the Gold Country using the power of hydraulic mining to expose the nuggets.)

“Although no history of Martinez that I (Bonnell) know of mentions this fact, Dr. Semple himself built one of our town’s first buildings probably in late 1848 or early 1849. It was wood frame structured named ‘Ferry House’ and was designed to provide shelter, refreshment, and, I (Bonnell) suppose, an opportunity to gamble for those awaiting the ferry. It probably was successful for Semple sold the business to James C. Ward of San Francisco for $2,000, a princely sum in that era, on November 3, 1849. (Editor’s Note: Ward Street is no doubt named after James Ward who would have been a business associate of Smith’s in the 1840s in San Francisco and one of the few ‘friends of Smith’ who may have contributed meaningfully to the growth of the new town in return for a street name. Well, a business associate with the last name of Green might have been more generous had not the flood of Easterners into California seeking gold including Philadelphians who might recognize Green as Paul Geddes, an employee of a Philadelphia Bank who had embezzled enough gold in the 1830s or 40s to set himself up as a successful and respected businessman in Yerba Buena. Before anybody could identify him, Green left San Francisco quickly to parts unknown but Martinez still has his street name. As for The Ferry House not being mentioned in any Martinez history, it may be that early researchers such as Charlene Perry didn’t know about it. But Charlene was also rigorous in sourcing any material she used so it is more likely to this writer that she saw it in a source the accuracy of which she could not be sure of and could not verify.)

“Part of Smith’s plan to develop Martinez included attracting industry, so, in 1849, he traveled to New York in an attempt to attract Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s operations to Martinez. A misunderstanding or disagreement with the Martinez family over the siting of that industry quashed the plan, but Benicia was after the same prize. Based on Semple’s San Francisco business partner Thomas Larkin’s political influence, the U. S. Congress designated Benicia as a Port of Entry, and in 1850 a Customs House was built in Benicia. The Pacific Mail Steamship Co. moved its operations from San Francisco to Benicia in 1850. Its shops, coal bunkers, dry docks, warehouses from San Francisco to Benicia in 1850. Its shops, coal bunkers, dry docks, warehouses and wharves were employing more than 100 men in 1850, and at the peak of its operations upwards of 1,000 men worked at the place. It moved back to San Francisco in 1869.

“The U.S. Army came to Benicia in 1849, (two companies of infantry), and in 1852 the Benicia Arsenal was established. In 1853 the State capital moved to Benicia (it had been in Monterey, San Jose, Vallejo and Sacramento earlier, and returned to Sacramento in 1854). But for pioneer visionary Robert Baylor Semple, things had charged.

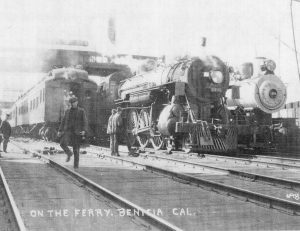

“Semple was appointed President of California’s first Constitutional Convention in mid-1848. When he returned to Benicia he was in poor health and the trip home worsened his condition. He was experiencing financial difficulties, and in mid-1849 he dissolved his partnership with Larkin exchanging his lots in Benicia (his original dream) for a ranch Larkin owned in Colusa County. Just as Benicia was taking off, a disillusioned Semple walked away. He allowed Oliver Coffin of Martinez to post a $2,000 bond and take over the ferry service across the Strait. Coffin, using a steam-powered scow, moved the ferry services’ southern landing to the foot of today’s Ferry Street.

“How did it all end for all those involved in Benicia and Martinez from 1846 to 1854? Sam Brannan played major roles in California history, prospered in the collapse of John Sutter’s New Helvetia, became California’s first millionaire but was virtually penniless when he died and was buried in a pauper’s field in San Diego County in 1889. Edward Von Pfister only remained in Coloma until October 1848, when he left to search for a man who had brutally murdered his brother in Sacramento. Unsuccessful in his search, he returned to Benicia in the spring of 1849 and there “lived out a good life in the esteem properly bestowed on such a solid citizen” until his death in the 1880s. Thomas Oliver Larkin took over Semple’s Benicia holdings, but fell arrears in taxes. He offered to make partial payment, was rejected, and then simply walked away from that city after virtually giving his land away. He did play a prominent role in California history until his death in 1858. (Editor’s note: Larkin was prominent enough to have a street in the San Francisco Civic Center on the north side of City Hall named after him. William Smith, who also had a big city dream for Martinez, also was in financial straits after his in-laws refused to agree to wooing Pacific Mail Steamship to locate on the Martinez waterfront. Depressed, he started drinking heavily and one evening in 1854, shot himself. One of the first to be buried in the new Alhambra Cemetery, first in the county, his grave was unmarked until just a few years ago as suicides were not permitted a grave stone in the 1800s.)

“Dr. Semple’s ending was the saddest of them all. Leaving his dream city behind, he moved with his wife in the ranch in Colusa County. Very little is known about his life after that move, but in 1854, at age 48, he was thrown from a horse on the ranch and died. When his body was disinterred for reburial shortly thereafter, the workers discovered that his body was wildly contorted in the coffin and there were splinters of wood under his fingernails from having tried to claw his way out of a premature tomb! It is said that his wife, shaken by what had happened, insisted upon being buried with an air pipe running down her coffin, and that her coffin be equipped with an alarm bell.

Editor’s Note: The distressing story about Robert Semple’s ending, while rare, was horrifying to many living then and to those of us who read about it now. Eleanor Roosevelt was so affected by whatever stories she had heard of this that for years she gave very strict instructions to her family and doctors that when she was declared to be dead all her veins were to be opened so there was no chance of such a horror happening to her.

Source: “A Semple Tale of Neighbors” article for the Martinez Historical Society newsletter, John Bonnell,

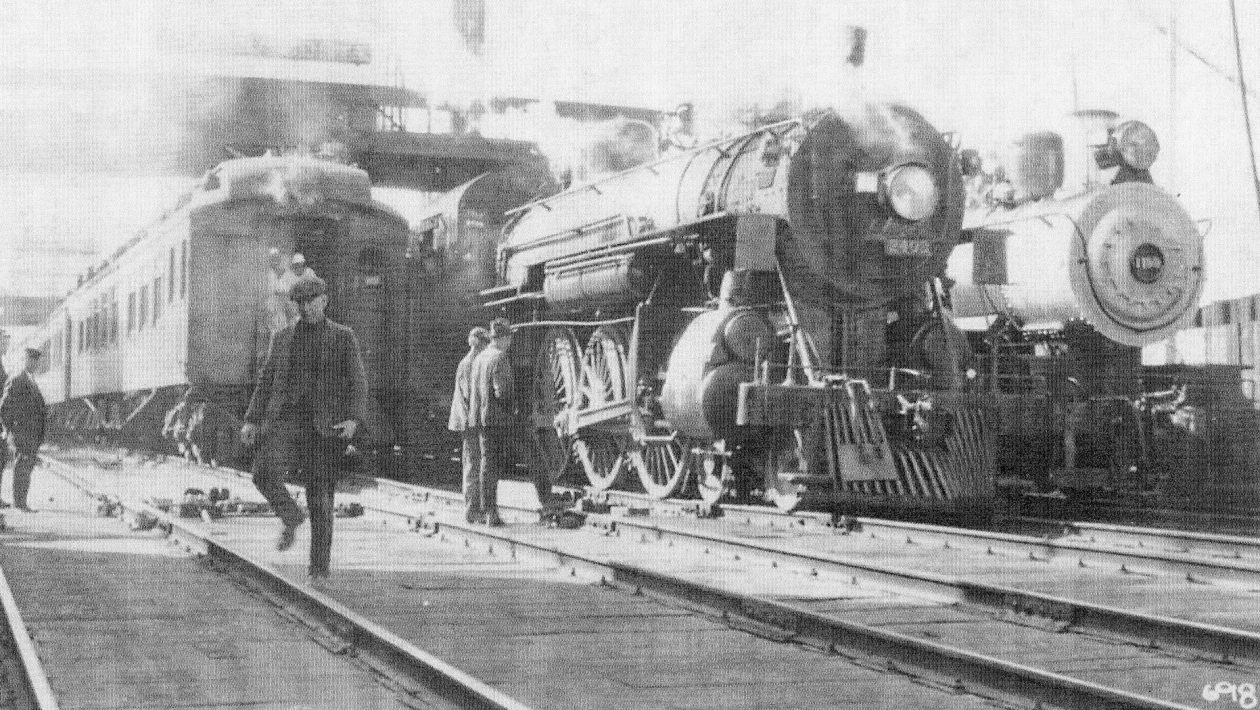

Martinez: A California Town, chapter 2, The Railroads page 21