There’s a lot more to know about him than we realize

By HARRIETT BURT

Martinez News-Gazette Contributor

Editor’s Note: There are so many interesting topics for a column like this. But just when this writer thinks she has a manageable list, a new idea pops up that can’t wait for a few months. Such is the case with this week’s column on Don Ignacio Martinez, upon whose rancho his eleven children and a son-in-law founded our town within a year of his death. Thanks to a short 1963 biography for the Contra Costa County Library by one of his great granddaughters, the late Kathryn Burns Plummer, there is much more information about the man who was Susana Martinez Hinckley Smith Merle’s father than I and many others realize. Don Ignacio was not just a name for the City Hall plaza or for the city with a 94553 zip code but also a diligent servant of Spain and later Mexico who was a very active participant in events in California between 1799 and 1839 when he retired to his Rancho el Pinole. This writer will use San Francisco as the settlement’s name as Mrs. Plummer did even though it was usually called Yerba Buena during the Mexican rule.

The King of Spain still owned and governed Mexico when Don Ignacio Nicanor Martinez was born in Mexico City in 1774. Since his father held the honorific “Don” by his name, he may have had a ‘civil service’ position in the colonial government.

In 1799, young Ignacio petitioned for appointment as a cadet in the Spanish Royal Army. The Viceroy of Mexico, Spain’s official representative and governor of the colony, soon assigned him as cadet to the Presidio of Santa Barbara in California (referred to as Alta or upper California, the current state).

Still a cadet three years later, Martinez married Dona Maria Martinez Arellanes in the chapel of the Royal Presidio. Her parents had arrived in California in 1776 as members of the party of 250 settlers brought from Mexico by Captain Juan Bautista de Anza. Her father, Don Manuel, had been a soldier who retired when his enlistment was up and later became Alcalde (mayor) of Los Angeles.

The Martinez newlyweds began their family with a daughter in Santa Barbara. In 1806, Don Ignacio was transferred to San Diego where they welcomed two more children including a son, Jose. Eleven years later the last Spanish governor of California promoted him to lieutenant of the Santa Barbara company. He had liked his previous posting there. It was where his second son, Vincente, was born. So he was not happy in 1819 when he was transferred to the Presidio of San Francisco where another daughter arrived soon thereafter. A few years later in 1827 the seventh and eighth children, twin daughters, Susana and Francesca, were born, followed in the next five years by three more daughters for a total of eleven offspring all of whom survived to adulthood although one of the daughters never married and died in her early 20s.

Don Ignacio served for 12 years at the Presidio. In 1822, two years after Mexico declared its independence from Spain, Lieutenant Martinez took the oath of allegiance to the new nation and continued his duties. His commanding officer, Luis Antonio Arguello, was elected governor and moved to the capital city of Monterey. Lt. Martinez succeeded him as “comandante” at the Presidio of San Francisco and moved his family into the official residence of the comandante. After California joined the United States, the presidio became an army base and the residence became its headquarters where it is still in use as part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Governor Arguello and members of the legislature drew up a plan for governance of Alta California which Lieutenant Martinez read to the troops assembled on the plaza of the Presidio.

During Don Ignacio’s tenure in San Francisco, Mexico’s first government led by Emperor Augustin I was overthrown in 1824 and replaced by a republic. Governor Arguello and members of the legislature drew up a plan for governance of Alta California which Lieutenant Martinez read to the troops assembled on the plaza of the Presidio.

Three years later Don Ignacio, with a priest, a dozen cavalrymen, an artilleryman with a cannon and a force of Christian Indians, went to Sonoma to establish the last mission, Mission of San Francisco de Solano, now surrounded by the city of Sonoma and famous as once the headquarters of General Mariano Vallejo’s land grant of most of Solano and Sonoma counties and the scene of the Bear Flag Revolt. However, seven years later, in August, 1834, Governor Figueroa issued regulations for the secularization of all the missions including Sonoma. Retired from the army by then, Don Ignacio was put in charge of the closing of Mission San Rafael. According to Mrs. Plummer, he spent three years on the project. He laid out the town of San Rafael and distributed 1,291 sheep and 439 horses among 343 Indians living in the community.

Ships from various European countries often entered San Francisco Bay to restock supplies and formally present themselves to the commandante. One of those 1824 was an Imperial Russian Navy ship whose commander, Captain Kotzebue, ordered the customary formal salute from his cannon before docking. But there was no reply which in naval etiquette was considered either rude or hostile. Lt. Martinez was in Monterey so his deputy sent a boat out to borrow gun powder so the Presidio could return the salute. The Russians bought provisions and the captain toured the settlement and two missions before he left for the Russian colony in northern California. He noted in his log that California would benefit a great deal if it were a Russian province and that it would also be useful to Russia.

In May, 1826 Don Ignacio investigated a charge in Mission San Jose that American immigrants, led by Jedediah Smith, were luring Indians away from the missions. The Don absolved the Americans of any blame. The same year, the pay of soldiers at the Presidio was eleven years in arrears. The Mexican government sought to solve the problem by sending a brig loaded with cigars. Don Ignacio refused to accept them.

Elected to the California Legislature in 1827 he was secretary pro-tem and a member of two committees. In 1829 Governor Echeandia suggested to the Secretary of War and Marines in Mexico City that Lieutenant Ignacio Martinez be promoted to Captain of the Company in Santa Barbara. Nothing happened and Don Ignacio was retired in 1831. He and his family moved to San Jose, then a Pueblo of 100 houses, , a church, a courthouse and a jail surrounded by orchards of fruit trees and fields of wheat and corn.

However, Don Ignacio’s contributions to California did not end in 1831. Almost immediately, two military companies were organized, each with 44 men. Martinez was Lieutenant of the second company. Their principle goal was to regain cattle and horses stolen from the citizens of the pueblo. The citizens were forbidden to pursue the thieves without an escort of troops.

In a busy retirement, Don Ignacio became an alderman of San Jose and secretary of the town council. In 1835, San Francisco (Yerba Buena) became an official town and elected its first alcalde (mayor). By that time Don Ignacio and his family were about to move to the completed adobe at Rancho el Pinole. By 1837 when he and Dona Maria were living at the Rancho, he became the third Alcalde of San Francisco. His eldest son, Jose, was commissioned lieutenant of the San Francisco militia. Don Ignacio went to Yerba Buena by boat to preside when meetings were held, probably using a boat, he had bought a boat from the Russians in 1823. It was likely built at their colony at Fort Ross out of timber from the neighboring hills. He paid 12 ‘fanegas’ of wheat for it. A ‘fanega’ is roughly the equivalent of an English bushel.

In 1839, the Don finished his term and except for a brief stint that year as a substitute in the Alta California legislature, that was his final participation in civic affairs. He retired to his Rancho el Pinole where he died on June 24, 1848 170 years ago this month. His grandson, Stephen Richardson, recalled in his 1935 memoirs, his grandfather’s casket being carried on a ‘carreta,’ a Spanish wagon with wooden wheels, drawn by a double yoke of black oxen. The funeral procession, winding its way to the Mission, stopped at the ‘haciendas’ (ranches) it passed. At each one, members of the family who lived there would join the cortege. Stephen figured the trip would have taken four or five days

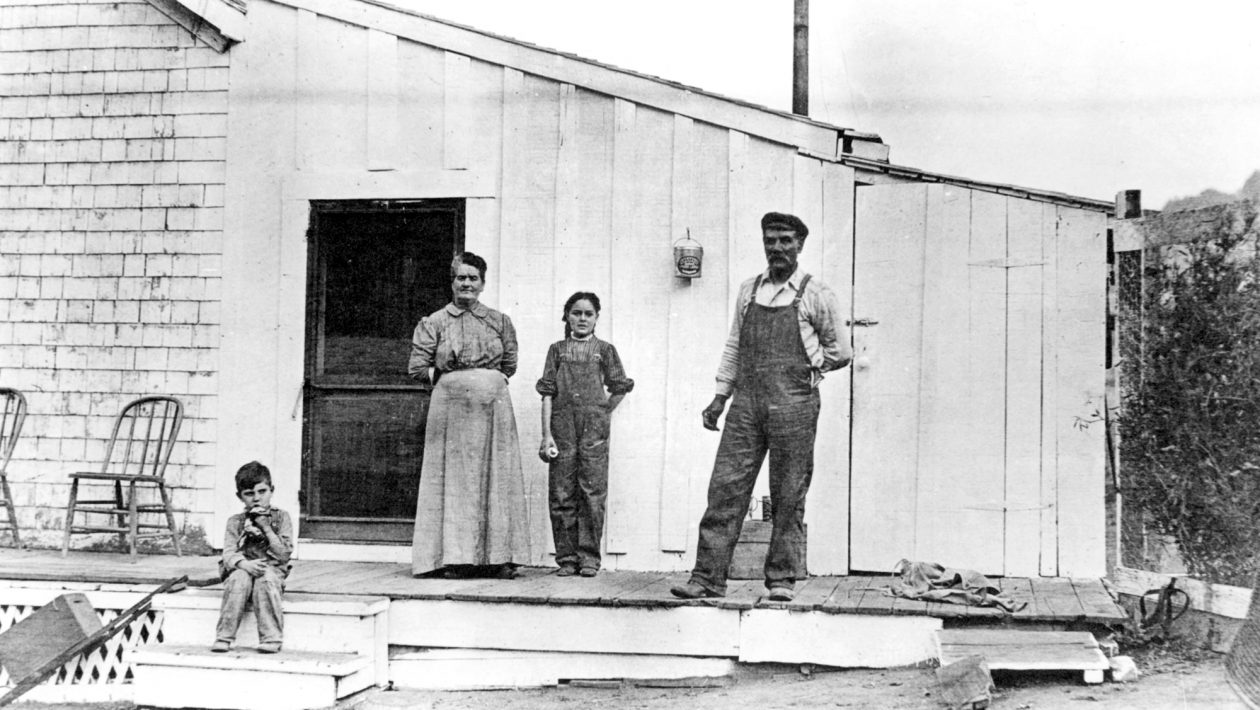

In 1963, Mrs. Plummer wrote, that pictures or portraits of all the Alcaldes and Mayors of Yerba Buena/San Francisco, were displayed in the outer offices of the Mayor in San Francisco City Hall. Don Ignacio was represented there. However, since the Don’s portrait was lost in the 1906 fire, the image in 1963 was of the Don’s younger son, Vincente, whose adobe still exists in Martinez.