By HARRIETT BURT

Martinez Gazette Contributor

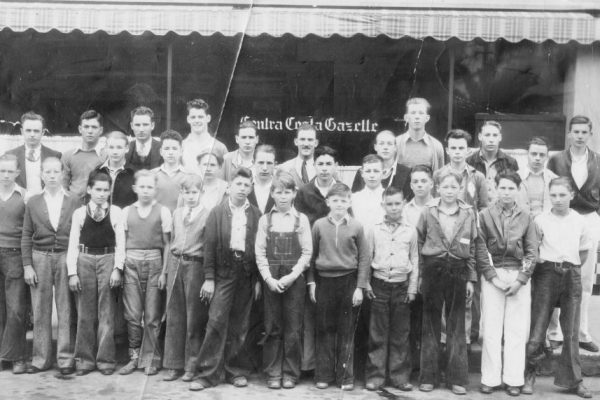

Last Sunday’s historic tour of the Italian fishing community in the late 19th and first half of the 20th century was sponsored by a group unfamiliar to this writer – the Italian American Studies Association. Founded in 1966 by a group of historians, educators, sociologists and other interested persons, the IASA focusses on “the interdisciplinary study of the culture, history, literature, sociology, demography, folklore, and politics of Italians in America.”

According to Lawrence DiStasi, a member who lives in Bolinas, IASA is a national organization divided into two regions, one in the East centering in Long Island and the Western Region which focusses on California, Arizona, Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Montana, and Idaho. Holding conferences from time to time such as one in Monterey some years ago studying the west coast fishing community, it takes tours such as the one on May 6 in Martinez. Papers on various aspects of the Italian-American experience are published and distributed by members at conferences and on the IASA website.

Members also pursue topics relating to the Italian-American/immigrant experience. DiStasi, for example, recently wrote a heavily researched book, “Branded: How Italian Immigrants Became ‘Enemies’ During World War II”. Italians, many of whom had lived here for decades but who had not obtained US citizenship were either personally touched or knew people who were forced to leave their homes along ocean and bay coastlines and live at least five miles inland. Allowed to find their own housing, most of them were permitted to return to their homes after six months in 1942.

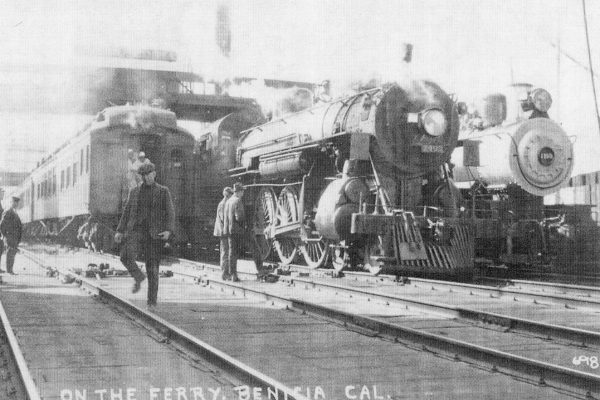

Italian fishermen were affected by this in a number of ways, some for longer than six months and many, if not all, financially, according to DiStasi. In the chapter on Italian Fishermen, DiStasi recounts the restrictions on all Italian fishermen whether citizens or not in the coastal areas including San Francisco Bay. Boats of a certain size were commandeered by the Navy who thought the boats with purse seiners (fish nets which were pursed or drawn into the shape of a bag that was weighted in the bottom and dropped straight into the water and pulled out closed to enclose the catch) could be used as submarine chasers. However, the boats couldn’t move away fast enough after dropping the depth charge to avoid damage.

Meanwhile, citizen owners such as Antone Pellegrini could apply for licenses for both of his boats and continue to fish in the Strait. But Antone’s parents, Luigi and Agusta, could not. So, they moved to Concord. Being a family business, there was no problem finding a job to be done outside the restricted zone. Luigi took over the county fish delivery route. Antone would deliver the fish to his father in Concord who then would sell it all over south central Contra Costa county. Once an Orinda rancher paid him with a steer. The steer was tied to the back of the truck which then crept back towards Concord. According to his son, Danny, Antone, worried when Luigi didn’t show up at the usual time, reversed the route and found him parked at a ranch on Reliez Valley Road. The owner agreed to allow the steer to stay there until a butcher came to take care of it.

Resourcefulness, even in the face of injustice, was a by-word of the Italian-American fishing life.

Sources:

Interview with Lawrence DiStasi, Interview with Danny Pellegrini. Lawrence W. DiStasi, “Branded: How Italian Immigrants Became ‘Enemies’ During World War II”, Chapter 6; copyright 2016, Sanniti Publications, P. O. Box 533, Bolinas, CA 94924. About the Italian American Studies Association.