By HARRIETT BURT

Martinez Gazette Contributor

In the little more than 25 years that Mexico ruled over the southern and central coast and neighboring inland area of California, the mission system was replaced by the land grant rancho system where over 600 grants of vast land holdings were made from San Diego to Petaluma and east from the ocean to the coastal range and neighboring valley, according to the late California historian, Kevin Starr.

Don Ignacio served for 12 years at the Presidio. In 1822 after Mexico declared its independence from Spain, Lieutenant Martinez took the oath of allegiance to the new nation and continued his duties among which were to meet applicants for land grants and supervise the location of those grants. According to Kathryn Burns Plummer, his first ‘informal’ survey of land in the East Bay came was the fixing of boundaries of the land grant in the Contra Costa (opposite coast from Yerba Buena now San Francisco) applied for by Sergeant Luis Maria Peralta. Martinez and two soldiers met Peralta, two of his sons and two soldiers at Mission San Jose. From there they traveled to San Leandro Creek to put Peralta in possession of his land and to determine the boundaries.

Peralta’s son later recorded the process of fixing of the boundaries:

“The Lieutenant took out the papers of my father’s title and proceeded to read them. He ordered to be brought some earth and then threw this earth toward the four winds. He ordered the soldiers who came as witnesses to discharge their muskets. The Lieutenant asked my father unto what point he wished to have possession. My father said that he wished possession given to him of the land which the deep Creek of San Leandro bounds. Then (the lieutenant) asked “Sergeant, unto what point northward do you wish possession given you?” my father said, “let us advance.” We went northward. When he arrived at the brook of “El Cerrito’, my father said, “unto this point, sir, I wish possession.

“Then we disposed ourselves to eat at the small willow grove beside the fresh water near the bay; but we did not eat there, because of the mosquitoes. To avoid them my father said, “let us go up to another spring where there is wind and it is cooler and no mosquitoes.” They went up the stream where there was fresh water and no mosquitoes and there ate lunch.”

Thus, El Cerrito creek and its brook became part of the boundary line between Alameda and Contra Costa counties. The land grant’s final boundaries were from San Leandro Creek to El Cerrito Creek and from the Bay to the top of the (Oakland) hills. And Peralta became a common name for locations and institutions in Alameda County long after the rancho ceased to exist.

In 1836, Don Ignacio Martinez turned over his duties and moved to his rancho in ‘the Contra Costa’. He had applied for the land grant in 1823 while commandant at the Presidio. It was for 3 sitios (three square leagues) to extend from San Pablo Bay through the Pinole Valley and over the hills to the Alhambra Valley, then know as La Canada del Hambre, and down that Valley on the west side of Arroyo del Hambre, now known as Alhambra Creek, to the Strait of Carquinez. He was granted a provisional title. When he was granted a cattle brand the next year, he sent his sons, Jose and Vincente, to the Rancho el Pinole with his cattle. They built a large adobe and planted a vineyard.

When the grant had not yet been formally approved in 1837, he applied again, this time for four leagues as he had more cattle. His petition was dated November 1837 from Rancho de la Merced, the name he had given the Rancho. According to Mrs. Plummer, there came to be 17,786.49 acres extending from San Pablo Bay looking across to Richardson Bay (named after a Martinez son-in-law) east to the vicinity of Franklin Canyon with a knob that spins off towards Carquinez Strait where the town of Martinez was later established. Formal receipt of the grant was made to the Don in 1842 by Governor Alvarado. At some point the name changed to Rancho el Pinole. Pinole is a native word for a type of flour made from seeds of corn chia and various other grasses and herbs. A local tribe fed pinole to a Spanish exploring expedition that had run out of food. The Spaniards named their camp El Pinole in remembrance.

According to the Images of America: Pinole book, the Don moved his wife, Dona Maria Arellanes and most of his 11 children to the Rancho in 1836 or so. When his sons married, they built adobe homes next to their father. Soon the three homes became known locally as Los Adobes of Pinole Viejo (old Pinole).

By 1839, the Don owned thousands of cattle, horses and sheep not to mention an orchard and a vineyard. Hides were taken by carreta (ox cart) to about three miles to Point Pinole and traded for supplies from Yankee ships. The Don kept the large boat he had used to go to Yerba Buena for his Alcalde duties there. He also kept a cannon on hand to ward off unfriendly Native Americans if needed. It was fired in celebration when his sons were married.

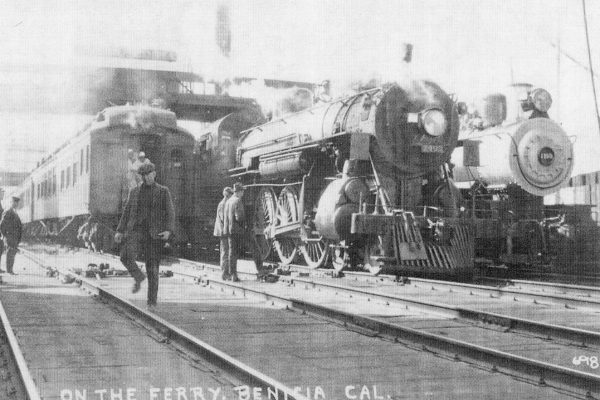

After the Don’s death, the rancho was left to the family. Vincente had built an adobe in what is now Martinez. Overnight during the Gold Rush, because of the Benicia ferry, Martinez became an important location on the route to the gold field from Santa Clara and Monterey counties. Susana Martinez’s husband, William Smith, convinced Jose Martinez to deed over the land and the family to hire Thomas Brown to survey it. The rest is Martinez history. It was also the beginning of the end of Rancho el Pinole. In the 1870s, the family either lost or sold off the remains of the original rancho. In the early 1900s, Vicente’s son, Ignacio, managed part of the former rancho for its then owner, Bernardo Fernandez. He and his wife and young daughter lived in one of the dilapidated adobes. Now the foundations are under the earth and the only pictures are from the 1920s when a combination of the 1906 earthquake and neglect had turned them into ruins.

Sources:

Kathryn Burns Plummer, Don Ignacio Nicanor Martinez, September 1963, Contra Costa County Library

Joseph Mariotti, George Vincent, Jeff Rubin, Pinole – Images of America, 2009, page 13

Kevin Starr, California – a history, Modern Library Chronicles, 2007, p. 49.