By HARRIETT BURT

Martinez News-Gazette Contributor

Editor’s Note: Recently digging through Martinez Historical Society archives of newsletter articles, I found a 1994 column by then Society president John Sparacino, former Mayor of Martinez and one of the handful of local folks most responsible for the founding and success of the Society and its Museum.

In fact, Mayor Sparacino was a key figure in the agreement with the Contra Costa Community College District not to tear down the 1890 Borland Home for an employee parking lot but to allow the Society to restore the building and create a museum of the city’s history with city support.

A savvy negotiator, Mayor Sparacino suggested providing a section of parking places on the east end of Parking Lot #4 for the CCCCD staff in exchange for the restoration and use of the Borland home. The City of Martinez is part of the agreement that includes a series of 15 year terms allowing the Society to use the building for a museum at a rental fee of $1 per year plus permission by the County to the City to install parking meters in one row of its parking lot on the east side of the museum.

In addition, the District works closely with the City and the Society on various matters and financed and completed a $250,000 project recently to construct a concrete foundation giving the Borland home permanent stability plus repair of such building ‘old age’ problems as dry rot.

According to Society President John Curtis, the combination of College District, City, County and the Society agreement has been a very positive example of how agencies and a community organization can work together for the benefit of all for over 40 years.

Sparacino kept in touch with Curtis every few months until very recently to make sure that things were going smoothly with the Museum and its partners. That is just one of his many contributions to ‘making things work’ in the community.

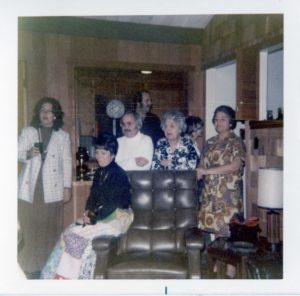

John Sparacino died at age 92 on April 3, 2018. 24 years earlier when he was Society president he wrote a column about life in Martinez during his childhood as part of a large family whose father was a prominent businessman in the fishing and banking community in the first five or six decades of 20th century Martinez.

In that August, 1994 MHS newsletter Sparacino explained he was the youngest of eight children. Johnny, as many knew him over the years, treasured his entire life in Martinez and the opportunities the town gave him in business and politics. Martinez has also been the the enduring seat of a large and close family he led who have never stopped loving and caring about their hometown.

Following is an abridged version of his column about Martinez.

President’s Message – MHS Newsletter, August, 1994

By JOHN SPARACINO

If you grew up in Martinez between the early 1920s and the mid-1940s, you probably have fond recollections about what a magical little town it seemed to be during that era. Certainly Martinez shared in America’s trials and tribulations during that twenty year period, but it nonetheless seemed happy and vigorous; its population more than doubled during that period (from about 3,500 in 1920 to more than 8,000 in 1945). Somehow Martinez seemed different and better than the many small Contra Costa communities that surrounded it.

Martinez had a generous share of festivals, parades, summer carnivals, Fourth of July and Christmas decorations, great high school sports teams, an exciting semi-professional baseball team that competed in the old Contra Costa County/Refinery League, and a wide variety of waterfront sports activities. Because it was the seat of Contra Costa County, it boasted a grand Court House and, from 1933 onward, an imposing Hall of Records (Editor’s Note: the 1903 Court House building is now the recently restored County Finance Building and the Hall of Records is the Wakefield Taylor Courthouse.) Martinez had good schools and some very dedicated teachers, friendly churches, and reliable and accommodating police and fire departments. Main Street was alive with commerce during the day, and Ferry Street was alive with socializing both day and night. It also had the State Theatre, a grand movie palace of the 20s and 30s, and a smaller theater, the Avalon, on Escobar Street (Ed Note: where the Community College headquarters and its parking lot are now located) which entertained us with Hollywood’s magic and brought us the news of the world in pictures.

But many towns in the then-predominantly rural United States could boast such assets. What made Martinez unique was a combination of five assets that no nearby town (and very few far-flung towns) could match: Martinez had railroads, ferry boats, a thriving fishing industry, a flourishing and diversified agricultural industry and a booming oil refining industry.

Many families used to go “down to the station” on warm summer evenings to watch the Southern Pacific trains and passengers pass through. I remember sitting on the station platform on an unused four-wheeled baggage cart, or on the hood or front fenders of the family car while you watched trains named Owl, Oregonian, Cascade, Klamath, Senator and the Valley or Shasta Daylight stop to discharge and take on passengers and baggage. I remember the thrill of watching a freight train highball through town coming off the downgrade from the Benicia (SP) bridge. I remember the friendly hobos passing through town during the depths of the Great Depression.

How many family outings to Lake Tahoe, the Napa Valley, the Sonoma coast, the Redwood Empire or similar destinations started and ended with a ride across Carquinez Straits aboard “the ferry” of which there were about six different ones in the 1920-62 period. I remember the clanging bells, the moan of the whistle, and the great rush of water as the ferryboat slammed into the wooden pilings of the ferry slip to end the twenty-minute crossing. Wasn’t the screeching of the seagulls and the fresh, raw wind in your face the stuff of children’s dreams?

Downstream from the Ferry and Court Street wharves, along the banks of Alhambra Creek where it finds its way through the tules to Carquinez Straits, was the heart of our town’s fishing industry. For almost 40 years prior to the 1920-45 era, the feluccas (Ed. Note: the traditional fishing boat of Sicilian fishermen was later replaced in California by a modified version called the Monterey), nets, buckets and canneries were an important part of the County’s prosperous fishing industry. The docks and canneries were beehives of activity during the seasons of shad, salmon, bass, sturgeon and sardines which ended in 1957 when the State of California closed Bay waters to commercial fishing.

The fertile soil of Alhambra Valley and Franklin Canyon created a century of successful farming that ended after the beginning of the suburbanization of Martinez in the late 1930s. But even after World War II, those farms were still shipping their rich harvests of fruit and berries to markets across America until the suburbs spread. At the height of the season from late June through mid-September, a parade of railroad boxcars would be switched down the spur track that ran from the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad’s Muir Station to Alhambra Valley Road (Ed Note: now Alhambra Way just before the Highway 4 underpass) and would come to rest alongside the three packing sheds to onload pears, peaches, cherries, plums, apricots and apples. Farmers’ trucks would line up waiting to unload their harvest at one end of the sheds. Inside, people and machines were busy washing, sorting, wrapping and packing the fruit for shipment to far-off markets. In early spring the incredibly sweet aroma of millions of fruit blossoms filled the air, and during the often dreary winter months, the rich, sweet smell of smoke curling up from piles of fruit tree prunings burning in the leafless orchards mixed with the fog to scent the Valley.

Despite repeated fires, explosions and an occasional strike, the two oil refineries in Martinez and nearby Avon have been good solid citizens. Moreover, just when the town’s fishing and agriculture industries began their decline the oil industry grew bigger and prospered. Many Martinez families have had three or more generations of oil company employees. Certainly the oil industry didn’t smell as good as the farming industry (as kids we used to refer to Shell Avenue as “the stinky road”), but it has been, is and will be one of our town’s greatest assets. (Ed Note: Sparacino lived long enough to see a dramatic change in the greatly reduced amount of pollution produced by Shell and in the refinery’s greater cooperation with the community as well as a huge increase in its direct involvement in supporting education and helping with other projects in the community and its organizations such painting the interiors and exteriors of the Martinez Museum, the Library and the Veterans Hall to name just a few examples.)

When I hear someone say “I’m certainly glad I’m not raising my kids today, with all the trouble around,” I kind of chuckle. All the nice things I remember about growing up in Martinez happened during the post world War I recession, Prohibition, the Stock Market crash, the Great Depression, the rise of Hitler and Mussolini, Pearl Harbor, World War II and the introduction of the Atom Bomb! If anyone thinks that was a nice time to raise kids, they’ve got another think coming. But our civic leaders, our teachers, our religious leaders and our parents took time to make the 1920-45 era nice, and that’s why we have fond recollections of growing up in Martinez. I wish as much for today’s children, because Martinez, although it has changed and will continue to change, can still be a nice place to grow up. Some day when you have time, bring your kids or your grandkids to the Martinez Historical Society’s Museum. Tell them about Martinez when you were a kid, and share the many pictures, exhibits and artifacts with them. That’s what the museum is for.

– John Sparacino, President

Memories of John Sparacino

There are probably hundreds if not thousands of memories and stories about John Sparacino and his impact on life in Martinez in his lifetime from family and friends, colleagues, political activists, political opponents, Martinez residents, people who did business with him at his men’s store or at the savings and loan branch he managed here and from constituents who sought his help or support or who wanted to change his mind on an issue. He would be the last to seek the applause from most of those stories even though it was positive. But he was very good at seeking votes to elective office. As City Council colleague Jim Thelen says, “he always had the best interest of the community” in mind.

“I served ten years with him. He was always an honorable man. He was a good guy to work with whether you agreed or disagreed with him. I was glad to know him as a councilman, mayor and as a person.”

Asked about Sparacino’s role in the construction of the Don Ignacio Plaza in commemoration of the 1976 centennial of Martinez and Bicentennial of the United States which this writer had always thought was major, Thelen replied that the Plaza had been the idea of Chief Planner Barry Whitaker. The council consisted of Thelen, Sparacino, Ted Radke, Elwon Lance and Jim Krause had agreed that replacing the empty gravel and weed covered former Martinez Elementary playground between the Boys and Girls Club and City Hall with a lovely plaza where citizens could relax and organizations could hold events was a great idea. “John was certainly a leading force on the project,” he added.

For Sparacino’s nephew, Bob, his uncle’s first electoral victory in 1966 “was a breath of fresh air” in council politics. “He was very community minded. He wanted to give back to the city he was born and raised in. In those days politics were different than now. You ran to give back to the city what you had enjoyed. He was a very honest guy. He was always very accessible as a councilman and as a mayor.”

“He always had an open ear and his word was his bond. If he said he’d do something, he did it,” his nephew added. “If he didn’t agree with you he’d say so.”

As a family member and the head of the family after the deaths of his father and older brothers, John Sparacino had an ‘understanding’ leadership style always keeping calm under pressure, says his nephew.

“He was very caring and loving. If you needed anything, he was there for you.” In that characteristic, John Sparacino typified the prime value of Sicilians, the importance of ‘la famiglia’…the family.

This writer’s experience with John centered partly around la famiglia and partly around plain old local politics. I first met John and his sisters, Rose and Nina, in 1965 when I rented a one-bedroom apartment on Richardson Street from him, down from the original Sparacino Victorian built by his grandfather at the end of the block next door to the current family home on Escobar. John owned a haberdashery on Main Street with his oldest brother, Nunzio, in those days and was just one year away from running for City Council for the first time.

Everything was fine, even after I moved to a larger apartment across downtown on Robinson Street next to the junior high. Fine that is until the local political climate changed radically with the rise of Nancy Fahden and Women For the Waterfront who single handedly cleaned up much of Granger’s Wharf and pressured the City Council “to do something now!!!” about the waterfront. That led to the Waterfront Park, the Radke Regional Shoreline named after Ted and Kathy Radke, and coincidentally, the rise of Martinez as the American center of bocce ball and famous around the world (literally) for bocce ball.

Why this is important to know is because Nancy Cardinalli Fahden’s family were well-known local Italian fishermen. And Nancy was about to step into county politics in a big way by being the first woman to run successfully for the Board of Supervisors, I supported her enthusiastically. I won’t go through all the ins and outs of that except to say that John was Nancy’s rival in an election or two and he and his sisters didn’t speak to me for a period of time around elections in the 70s and 80s. Meanwhile, I decided to run for Council myself in 1992, long after John had retired from Council and Nancy from the Board. I did not seek John’s endorsement as we still existed in parallel universes.

I was elected and served for one term. At the end of that term, I got a new job as deputy chief of staff for the chair of the State Board of Equalization. My office was in Hayward and my duties including managing the office and handling the bulk of consumer calls needing help with various problems they had with the Board. Add to that a commute which was much longer than 12 blocks and weekend meetings and events I was expected to attend. I knew that with this job, if re-elected I could not adequately fulfill my duties as a Council member especially since we were in a massive fiscal crisis. The Sheriff of the time was pushing hard to get the Council to close down the Police Department and use contracted law enforcement from his Department. My thought about that was ‘over my dead body’ which I said out loud at a Council meeting earning a copy from said Sheriff of a nasty fund-raising letter he wrote mentioning my name unfavorably, etc. That angered me enough to almost cause me to change my mind and run. But I knew I could not, as if elected I could not adequately serve.

Not long after my decision was made public and while there was still time to file to run again, I received an unsigned typewritten letter praising my work as a member of the Council, noting my dedication to the interests of the people (which had lost me the support of one or more big donors) and urging me to run for re-election because the town needed people like me in office. It took me a little while but I finally figured out that it had to be from John Sparacino.

Some years later, when our friendship had long since been re-kindled and his interest in what was going on in town was as keen as ever, I told him about receiving the letter and figuring out that he had written it. I told him that I had kept it and how much it meant to me. He unconvincingly denied writing it and changed the subject. I have brought it up a few times since including recently. He still brushed it off and changed the subject but with a smile. I am so glad I mentioned it.

I have come to appreciate how much John loved this town and that while we didn’t agree on some ways to strengthen it, we both shared that love and the feeling that the best interests of all the people of the Martinez community comes above everything else when you are entrusted by them with a council seat.